CONTENTS

1. Warm-up: Map comparison; Inferences 1; Inferences 2

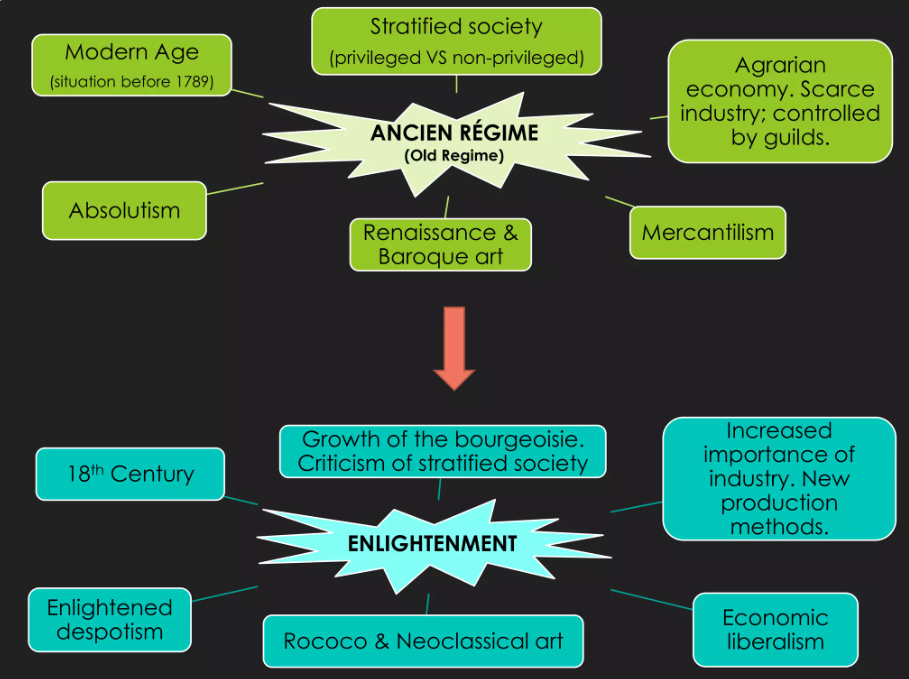

2. Defining Ancien Régime

3. The Enlightenment

4. Political Changes

5. Economic changes

6. Society in the 18th century

7. The 18th century in Spain

8. Presentations

9. Worksheets

1. WARM-UP

MAP COMPARISON

INFERENCES 1

What can you infer from these pictures regarding the 18th century?

INFERENCES 2

"Es sólo en mi persona donde reside el poder soberano, cuyo carácter propio es el espíritu de consejo, de justicia y de razón; es a mí a quien deben mis cortesanos su existencia y su autoridad; la plenitud de su autoridad que ellos no ejercen más que en mi nombre reside siempre en mí y no puede volverse nunca contra mí; sólo a mí pertenece el poder legislativo sin dependencia y sin división; es por mi autoridad que los oficiales de mi Corte proceden no a la formación, sino al registro, a la publicación y a la ejecución de la ley; el orden público emana de mí, y los derechos y los intereses de la Nación, de los que se suele hacer un cuerpo separado del Monarca, están unidos necesariamente al mío y no descansan más que en mis manos."

Discurso de Luis XV al Parlamento de París el 3 de marzo de 1766.

“Por tanto, si se aparta del pacto social lo que no pertenece a su esencia, encontraremos que se reduce a los términos siguientes: cada uno de nosotros pone en común su persona y todo su poder bajo la suprema dirección de la voluntad general; y nosotros recibimos corporativamente a cada miembro como parte indivisible del todo (...).

No siendo la soberanía más que el ejercicio de la voluntad general, jamás puede enajenarse, y el Soberano, que no es más que un ser colectivo, no puede ser representado más que por sí mismo (...).

¿Qué es, pues, el gobierno? Un cuerpo intermediario establecido entre los súbditos y el Soberano para su mutua correspondencia (...) De suerte que en el instante en que el gobierno usurpa la soberanía, el pacto social queda roto, y todos los simples ciudadanos, vueltos de derecho a su libertad natural, son forzados, pero no obligados, a obedecer. (...)

La soberanía no puede estar representada, por la misma razón por la que no puede ser enajenada; consiste esencialmente en la voluntad general, y la voluntad no se representa; es la misma o es otra; no hay término medio. Los diputados del pueblo no son, pues, ni pueden ser sus representantes, no son más que sus mandatarios; no pueden concluir nada definitivamente. Toda ley no ratificada por el pueblo en persona es nula; no es una ley. El pueblo inglés cree ser libre, y se engaña mucho; no lo es sino durante la elección de los miembros del Parlamento; desde el momento en que éstos son elegidos, el pueblo ya es esclavo, no es nada.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau. El contrato social. 1762.

"In the period of which we speak, there reigned in the cities a stench barely conceivable to us modern men and women. The streets stank of manure, the courtyards of urine, the stairwells stank of moldering wood and rat droppings, the kitchens of spoiled cabbage and mutton fat; the unaired parlors stank of stale dust, the bedrooms of greasy sheets, damp featherbeds, and the pungently sweet aroma of chamber pots. The stench of sulfur rose from the chimneys, the stench of caustic lyes from the tanneries, and from the slaughterhouses came the stench of congealed blood. People stank of sweat and unwashed clothes; from their mouths came the stench of rotting teeth, from their bellies that of onions, and from their bodies, if they were no longer very young, came the stench of rancid cheese and sour milk and tumorous disease. The rivers stank, the marketplaces stank, the churches stank, it stank beneath the bridges and in the palaces. The peasant stank as did the priest, the apprentice as did his master's wife, the whole of the aristocracy stank, even the king himself stank, stank like a rank lion, and the queen like an old goat, summer and winter. For in the eighteenth century there was nothing to hinder bacteria busy at decomposition, and so there was no human activity, either constructive or destructive, no manifestation of germinating or decaying life that was not accompanied by stench.

And of course the stench was foulest in Paris, for Paris was the largest city of France. And in turn there was a spot in Paris under the sway of a particularly fiendish stench: between the rue aux Fers and the rue de la Ferronnerie, the Cimeti?re des Innocents to be exact. For eight hundred years the dead had been brought here from the H?tel-Dieu and from the surrounding parish churches, for eight hundred years, day in, day out, corpses by the dozens had been carted here and tossed into long ditches, stacked bone upon bone for eight hundred years in the tombs and charnel houses. Only later-on the eve of the Revolution, after several of the grave pits had caved in and the stench had driven the swollen graveyard's neighbors to more than mere protest and to actual insurrection-was it finally closed and abandoned. Millions of bones and skulls were shoveled into the catacombs of Montmartre and in its place a food market was erected.

Patrick Süskind. El Perfume.

2. DEFINING ANCIEN RÉGIME

DEEP THOUGHTS: A POISONED DART TO THE ANCIEN RÉGIME FROM CONDORCET

- What is the main idea?

- What enlightened ideas are implied?

- Let's say you are Luis XV of France. How would you respond to Condorcet?

"Our hope for the future of the human species can be reduced to three important points: the destruction of inequality among nations, the progress of of equality within a same people, and finally, the authentic improvement of man. Thus, the day will come when the Sun will shine on the Earth on only free men who have no other master than their own reason"

SPREAD OF ENLIGHTENMENT: ENCYCLOPÉDIE

4. POLITICAL CHANGES

Voltaire. Cartas filosóficas. 1734

B.

“Hay que estar loco para creer que los hombres han dicho a otro hombre, su semejante: te elevamos por encima de nosotros porque nos gusta ser esclavos. Por el contrario, ellos han dicho: Tenemos necesidad de vos para mantener las leyes a las que nos queremos someter, para que nos gobiernes sabiamente, para que nos defiendas. Exigiremos de vos que respetéis nuestra libertad.”

Federico II de Prusia. 1871.

C.

"Dios establece a los reyes como sus ministros y reina a través de ellos (...). Actúan, pues, como ministros de Dios y son sus lugartenientes en la tierra.

(...) Sin autoridad absoluta, el rey no podría hacer el bien ni reprimir el mal. Es preciso que su poder sea tal que nadie pueda escapar a él (...). Cuando el príncipe ha juzgado, ya no hay otro juicio. los juicios soberanos se atribuyen a Dios mismo (...). Cuando Josafat estableció jueces para el pueblo dijo: "No juzguéis en nombre de los hombres, sino en nombre de Dios" (II Crónicas, 19, 6) (...).Solo Dios puede juzgar sus juicios y sus personas."

Jacques B. Bossuet: Política sacada de las Sagradas Escrituras, l679.

REAL THINKING: Venn Diagramm (3 circles)

COMPARE THE THREE SYSTEMS

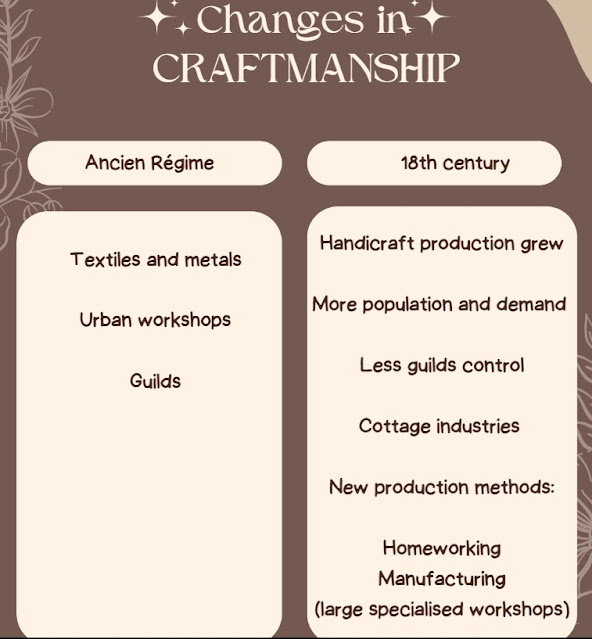

5. ECONOMIC CHANGES

FROM MERCANTILISM TO PHYSIOCRACY AND LIBERALISM

NEW ECONOMIC POLICIES THROUGH TEXTS

"...III. Earth, Agriculture, Sole Source of Riches. Let the sovereign and the nation never lose sight of the fact that the earth is the sole source of all riches, and that it is agriculture which multiplies riches. For it is the augmentation of riches that assures the wealth of the population; men and wealth cause agriculture to prosper, extend commerce, animate industry, increase and perpetuate all wealth. Upon that abundant source of wealth, agriculture, depends the success of all the parties concerned in the administration of the kingdom.

IX. Preference for Agriculture. Let a nation which has a large territory to cultivate and the facilities to carry on a large commerce with the land's products not use too much of the people's money in the manufactures and in the commerce of luxuries to the prejudice of labor and agricultural investments; for above all, the kingdom would well be a people of rich agriculturists.

XXV. Complete Liberty in Commerce. Let there be complete liberty in commerce; for the surest, most exact, and most profitable policy for interior and exterior commerce of the state and nation consists in the greatest possible freedom in competition."

Quesnay, F .General Maxims for the Economic Government of an Agricultural Kingdom. 1767

"The actual price at which any commodity is commonly sold is called its market price...The market price of every particular commodity is regulated by the proportion between the quantity which is actually brought to market, and the demand of those who are willing to pay the natural price of the commodity [demand]."

Quesnay, A. The wealth of nations. 1776

6. SOCIETY IN THE 18TH CENTURY: THE RISE OF THE BOURGEOISIE AND THE INFLUENCE OF THE ENLIGHTENMENT

ANCIEN RÉGIME

.png)

0 Comentarios