Europe in transition: from the medieval world to the Early Modern Age

Between the 15th and 16th centuries, Europe changes the way it thinks, creates and explores. Trade, Humanism, the Renaissance, science and navigation open a new historical era.

1. Europe in the 15th century: a continent in change

At the end of the Middle Ages, Europe grows slowly and remains a predominantly rural continent. But long-distance trade, cities and contact with the East open the way to the Early Modern Age.

“In the lands of the East there is an abundance of spices, such as pepper and ginger, as well as other rare and very valuable goods that are not found in Europe. Merchants travel great distances to obtain them, for they are highly valued both for their flavour and for their value in trade. In addition, these regions possess gold, precious stones and silks of great quality. The cities are rich and full of markets where products from many different places are sold. All this demonstrates the great wealth of these lands and the importance of the trade routes that connect them.”

The Book of the Marvels of the World (adaptation). Circa 1298

Check

- Population: slow growth; recent crises are still noticeable.

- Estate-based society: nobility and clergy / peasantry and bourgeoisie.

- Economy: agrarian base and guild craftsmanship.

- Luxury trade: silk, spices and porcelain.

- Cities: markets and the mercantile bourgeoisie grow.

2. Humanism: a new way of thinking

Humanism places the human being and the ability to reason at the centre. Classical texts are recovered, education is valued, and ideas spread thanks to the printing press, academies and universities.

Key ideas of Humanism (very clear)

- Anthropocentrism: the human being as the centre of interest (without “erasing” religion).

- Reason and observation: checking and arguing are valued, not just repeating.

- Classics: Greco-Roman works are studied (language, philosophy, history).

- Education: education is considered a tool to improve society.

- Vernacular languages: texts are written in local languages (Castilian, French, Italian…).

“Men are not born for ignorance, but to seek knowledge and virtue.”

“I have given you, Adam, neither a fixed place nor a definite form, so that you may choose your own destiny. The other beings have a determined nature; you, on the other hand, can decide who you want to be. You can fall to the lowest or rise to the highest, according to your will.”

Guided activity: commentary on a humanist text (step by step)

- Identify: is it a religious, political or educational text? Justify.

- Ideas: What is the source? and the author? and the date?

- Ideas: what is the text about?

- Ideas: write 2 main ideas of the fragment.

- Concepts: what humanist ideas appear?

- Concepts: What relation does it have with the period?

- Concepts: Debate: Is it more dangerous not to know or not to want to think?

Comparison of mindsets: Middle Ages vs Humanism

Read the two historical texts and compare them. Then open the drop-down and answer.

Source: De contemptu mundi (12th century)

The human being is born weak and full of miseries. His life on Earth is full of pain, work and temptations. Nothing that exists in the world is truly worthy of love, because everything is fleeting and leads to sin. True life is not here, but in heaven. Therefore the prudent man must not trust himself, but obey God and despise the vanities of the world.

Source: Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486)

We have given you, O human being, neither a fixed place nor a proper form, so that you yourself may choose and build your destiny. You may degrade yourself and live like an animal, or rise through your intelligence and your will to the divine. The human being is an admirable creature because he has the freedom to shape himself and achieve knowledge.

Critical thinking activity — Compare worldviews

- How does each author describe the human being?

- What role does God have in each text?

- What attitude towards the material world is proposed?

| Question | Text A | Text B |

|---|---|---|

| Is the human being weak or capable? | ||

| Must he obey or choose? | ||

| Is the world negative or valuable? |

- Which vision of the human being seems more optimistic? Why?

- Which text values knowledge more? Explain with words from the text.

- Which would fit better in an age of scientific and artistic advances?

- What characteristics of Humanism can you infer only by reading Text B?

Summarise in 3 main differences how the worldview changes between the medieval mindset and the humanist one.

Activity: Humanism detectives

Objective: discover humanist ideas in two sources and compare their authors using critical thinking.

The teacher enters saying:

“Europe is changing… but we do not know why. We need detectives to discover what new ideas are appearing.”

You work in pairs. Each pair receives the two texts (Pico and Erasmus).

- 🟢 Underline in each text one idea about freedom.

- 🔵 Underline one idea about education or knowledge.

- 🟠 Underline one idea that breaks with the medieval mindset.

- What main idea does Pico defend?

- What main idea does Erasmus defend?

- How are they similar?

- How are they different?

“A medieval group accuses these authors of being dangerous because they make people think too much.”

- Are they really dangerous?

- Why might their ideas have been disturbing in their time?

- Do you think that today someone could be afraid that people think too much?

3–4 short interventions are collected.

Write on the board:

“Humanism did not destroy Europe. It made it think.”

Check

Which statement best describes Humanism?

“Humanism was not only a cultural style, but a way of studying: reading, comparing manuscripts, searching for errors, discussing and improving knowledge...”

Activity: explain how this way of studying differs from “memorising without discussion”. (Pedagogical synthesis based on manuals of European Cultural History).

3. The Renaissance: a new art (and a new way of seeing)

The Renaissance arose in Italy and was inspired by Classical Antiquity. It sought beauty, proportion and harmony. Patrons (rich families, popes, princes) financed artists to demonstrate prestige and power.

- Classical inspiration: columns, pediments, semicircular arches, domes.

- Proportion and symmetry: buildings “to a human scale”.

- Perspective: representing depth (especially in painting).

- Naturalism: more realistic bodies and faces; interest in anatomy.

- Patronage: art as political and social prestige.

“Beauty is born from harmony and proportion among the parts.”

Change period and slide through the works. Click one to view it large.

15th century: proportion, perspective, recovered classicism.

16th century: monumentality, balance, great masters.

Mid-late 16th century: elegance, tension, artificiality.

I learn to look: compare (medieval vs Renaissance)

- Form: do vertical lines predominate (height) or horizontal ones (balance)?

- Decoration: very overloaded or more “ordered”?

- Elements: pointed arch (Gothic) or semicircular arch (classical)?

- Message: does it impose fear / mystery or convey serenity / rationality?

Observe body, space, light and emotion. What changes compared with medieval art?

Great families and popes financed works to beautify cities, churches and palaces. Art is not only beauty: it is also a political message.

Mini-task: “You are a patron”

- What do you want to show: faith, power, wealth, culture...?

- What city would you place it in?

- How would you like people to remember you?

4. The advance of science and technology

Between the 15th and 16th centuries, Europe transformed the way it observed the world. Greater confidence in reason, the spread of books and the use of instruments allowed scientific and technical progress that changed study, navigation and the image of the universe.

A new way of knowing

- Observation: looking carefully at nature (sky, human body, plants…).

- Measurement: numbers, tables, instruments.

- Experiment: testing an idea to see whether it works.

- Dissemination: books and printing press → ideas circulate faster.

He proposed that the Earth revolves around the Sun (heliocentrism).

“At the centre of all things rests the Sun.”

He revolutionised anatomy by studying the body through direct observation and detailed drawings.

“I have described the body as it is shown to the eye, not as books repeat it.”

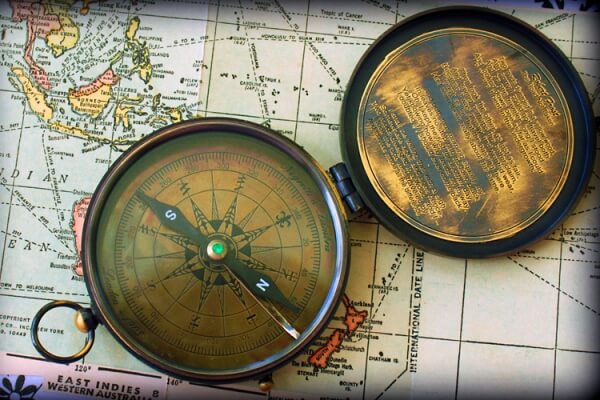

Instruments that changed voyages

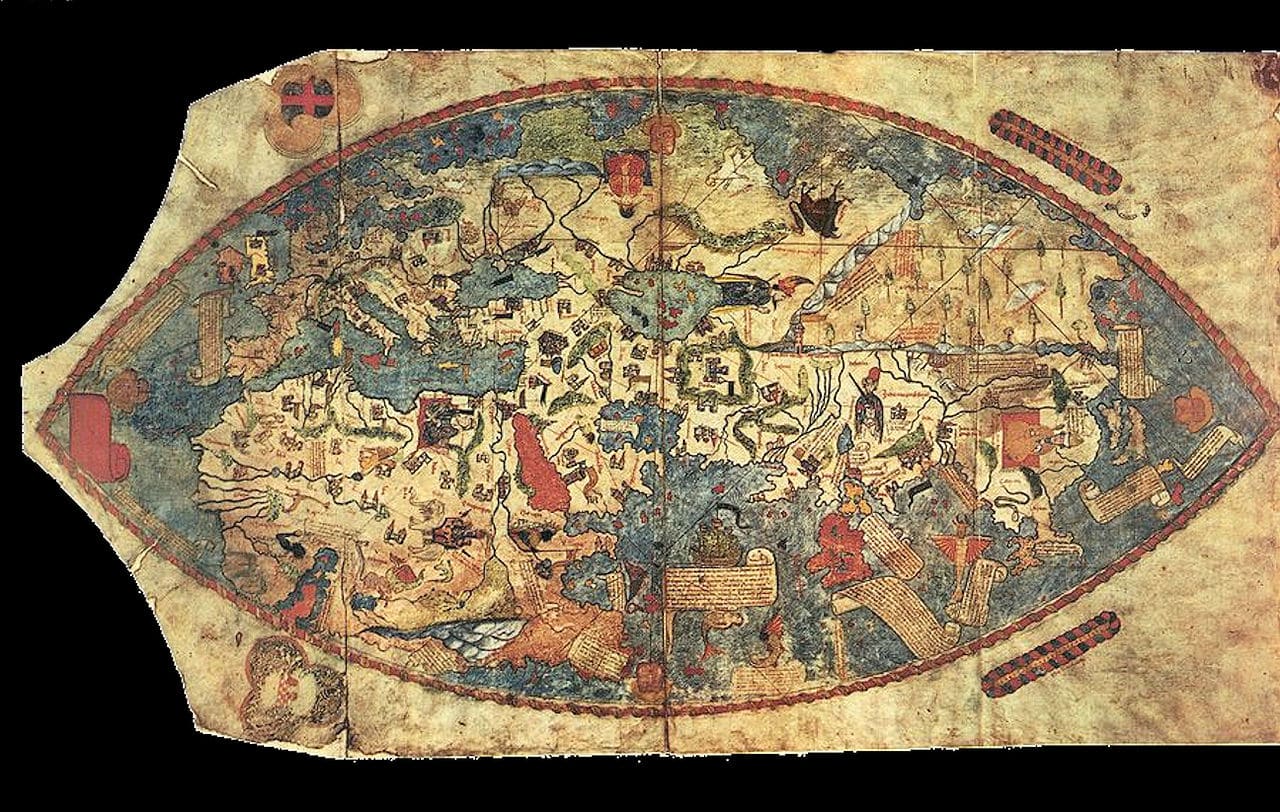

Projections help represent the Earth. In navigation, this changes route planning.

Critical thinking question: which parts of the world “seem” larger?

Observe Greenland, Europe and Africa. Do you think the map represents real size equally? Why would a projection useful for navigation matter even if it distorts areas?

The “scientific revolution” was not a single day: it was a process. The important thing is the change of method: from authority to evidence.

Task: write an “Before… / Now…” sentence (e.g.: “Before X was believed by tradition; now it is checked through observation”).

Match: instrument → what it is used for

Select the correct function and click “Check”.

5. Portuguese explorations: towards the route to India

Portugal began a maritime project to reach Asia by sailing around Africa. Little by little, it explored the coast, improved navigation and opened new trade routes. In 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India.

Why did Portugal explore?

- Trade: obtaining spices and products without so many intermediaries.

- Routes: seeking a sea route alternative to the Mediterranean.

- Geographical advantage: access to the Atlantic and maritime experience.

- Political drive: support from the monarchy and figures such as Henry the Navigator.

Timeline (very visual)

Key idea: progress comes step by step (coasts, stopovers, maps, experience).

“We found great markets and merchandise; and we understood that the voyage could bring Portugal wealth and power if the route were maintained.”

Competency-based activity: “Design your route” (map + decisions)

- Choose 4 stopovers: Madeira/Azores · Cape Verde · Gulf of Guinea · Cape of Good Hope · East African coast.

- Explain 2 risks: storms, currents, lack of water, disease.

- Explain 2 solutions: stopovers, supplies, improvement of the ship, expert pilots.

Final product: an itinerary with arrows on a map (photo or drawing).

It combines lateen sails (manoeuvrability) and square sails (speed with favourable wind).

Guiding question: what is more important for exploration: technology or organisation?

- Expensive spices → …

- Alternative route around Africa → …

- More knowledge of navigation → …

- New territories and routes → …

Activity: Navigation instruments

Identify compass, astrolabe and nautical charts.

Create/use activity6. Castilian explorations and America before Columbus

At the end of the 15th century, Castile embarked on the exploration of the Atlantic Ocean in search of new trade routes. This process culminated in the voyage of Christopher Columbus and the encounter with a continent that was already inhabited by numerous civilizations.

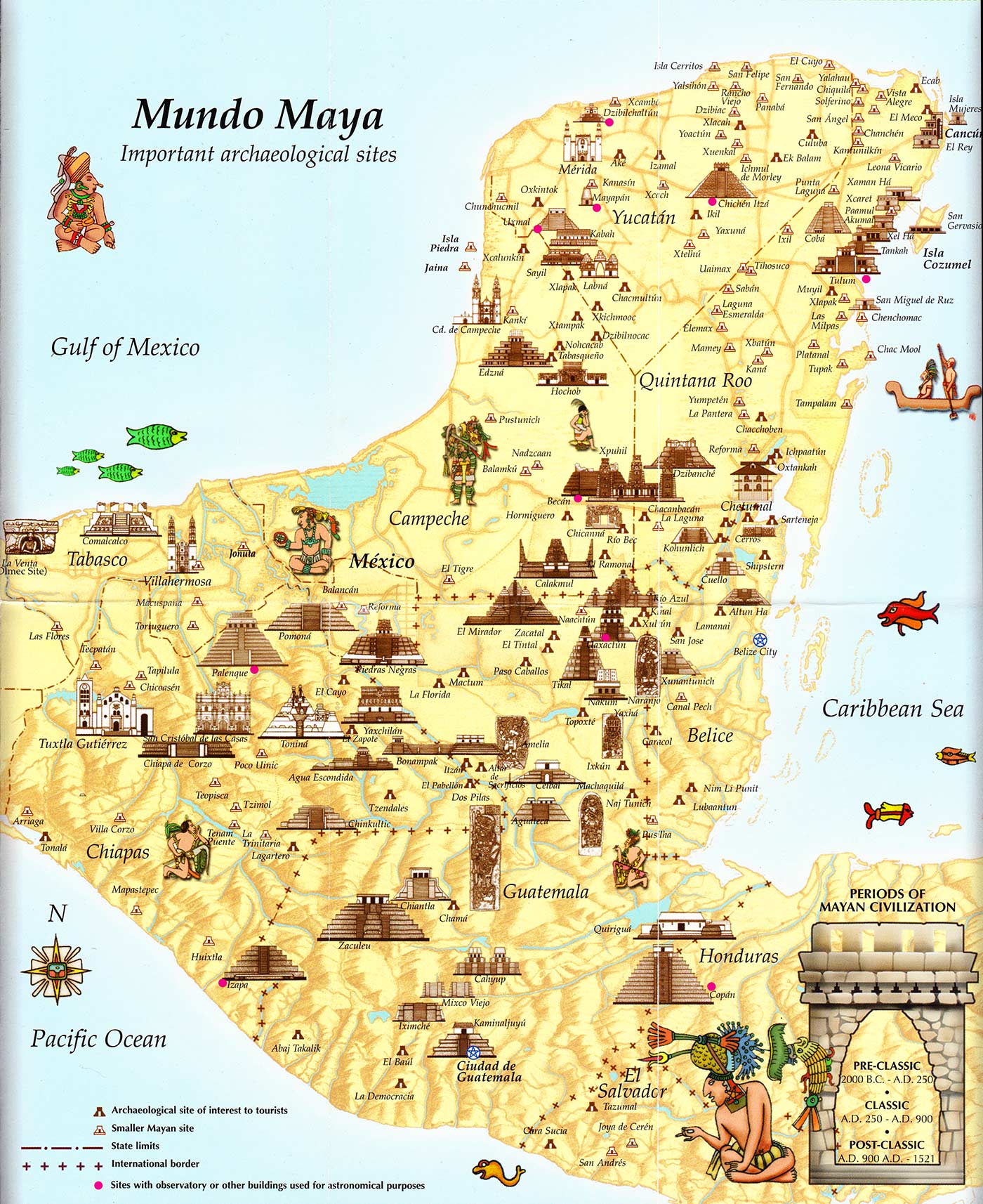

In 1492, the American continent was inhabited by numerous peoples, known as pre-Columbian, because they lived there before the arrival of the Europeans. Some, such as the Taíno or the Caribs, had simple ways of life; others developed great civilizations.

Three great empires stood out: the Maya, the Aztec and the Inca. They built cities, temples and roads, practised agriculture and developed a rich culture based on religion, trade and political power.

“ In the name of Their Highnesses, the King and Queen of Castile and Aragon. First: that Don Christopher Columbus be appointed Admiral in all the islands and mainland territories that he discovers or gains in the ocean seas, forever and ever, with the same honours and privileges held by the High Admiral of Castile. Likewise, that he be Viceroy and Governor-General in all the said lands...”

“ In the name of Their Highnesses, the King and Queen of Castile and Aragon. First: that Don Christopher Columbus be appointed Admiral in all the islands and mainland territories that he discovers or gains in the ocean seas, forever and ever, with the same honours and privileges held by the High Admiral of Castile. Likewise, that he be Viceroy and Governor-General in all the said lands that he discovers or gains, and that he may propose to Their Highnesses the persons who are to hold the offices in each place. Item: that of all and any merchandise, pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices and any other things and goods that are bought, exchanged or found within the bounds of his admiralty, he may have and take for himself the tenth part (the tenth part of everything), expenses deducted. Likewise, that if lawsuits or disputes should arise in the said lands, he shall have authority to judge them in his office as Admiral. Item: that he may contribute with the eighth part of the expenses of any fleet made for the said discovery, and that he shall also receive the eighth part of the profits resulting from it. All of which Their Highnesses promise to fulfil and observe, and order that Don Christopher Columbus be given his signed letters and privileges.”

Advice: maximise the browser (full screen) to read it all comfortably.

Critical thinking activity — The Capitulations of Santa Fe

- What type of text is it: narrative, legal, political, economic…? Justify your answer with phrases from the text.

- Who grants the privileges and to whom?

- At what historical moment is it signed? What was happening in the Peninsula in 1492?

- Why do you think Columbus demands that the office of Admiral be “forever and ever”? What does that mean in practice?

- What political powers does he obtain besides the economic ones?

- How important is it that he receives a tenth part of the riches? Do you think it is little or a lot? Explain your answer.

- Why do the Monarchs accept these conditions if the voyage has not yet succeeded?

- What does this document tell us about the economic mindset of the time?

- What role does the monarchy play in Atlantic expansion according to the text?

- Is it only a scientific project or are there other interests? Explain which ones.

- What risks did the Monarchs assume and what risks did Columbus assume?

- Do you think this agreement shows that the expansion was improvised or well planned? Argue your answer.

- How does this document fit into the process of formation of authoritarian monarchies?

- What relationship does it have with the competition between Castile and Portugal?

- What consequences did this agreement have after the discovery of America?

- When Columbus returned from his first voyage, were all these promises fulfilled without conflicts? Research and explain briefly.

Write a final paragraph explaining what this document reveals about how European expansion began and what interests lay behind Columbus’s voyage.

“To avoid disputes over the lands discovered in the Atlantic Ocean, the kings of Castile and Portugal agreed to draw an imaginary line from north to south 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. All lands discovered west of that line would belong to the kings of Castile. All lands discovered east of that line would belong to the kingdom of Portugal.”

The treaty was signed on 7 June 1494 in the Castilian town of Tordesillas and aimed to avoid conflicts between the two main maritime powers of the period.

Historical source analysis activity — The Treaty of Tordesillas

- What type of document is it: political, economic or religious?

- Which two kingdoms sign this agreement?

- Why do you think they needed to sign a treaty before exploring new territories?

- What does it mean that the world is divided by an imaginary line?

- What advantages did Castile obtain with this agreement?

- What advantages did Portugal obtain?

- Do you think this agreement took into account the peoples who were already living in America? Justify your answer.

- What other European countries might have felt harmed by this treaty?

- Why do you think that in America almost all countries speak Spanish except Brazil?

Write 3-4 lines explaining how this treaty influenced European expansion and the political organisation of America in the following centuries.

Christopher Columbus intended to reach Asia by sailing westwards. After presenting his project in Portugal without success, he obtained the support of the Catholic Monarchs.

Critical thinking question: What information does the map show and what important information does it not show about Columbus’s voyages?

What historical consequences can be inferred just by observing the routes on the map?

During the 15th century, Castile and Portugal competed for the control of maritime routes and the territories that might be discovered. Both kingdoms sought to reach Asia in order to trade in spices, silk and other valuable products.

To avoid conflicts, the Catholic Monarchs asked the pope to decide to which kingdom the discovered lands would belong. Finally, Castile and Portugal signed in 1494 the Treaty of Tordesillas. This agreement established an imaginary line in the Atlantic Ocean:

- The lands located to the west of the line would belong to Castile.

- The lands located to the east would belong to Portugal.

Thanks to this agreement, Castile began the conquest of a large part of America, while Portugal consolidated its presence in Africa, Asia and Brazil.

Simple interactive map — Understanding the Treaty of Tordesillas

Hover over or click on each area to interpret the division of the Atlantic.

Historical analysis activity — The division of the world

- Which ocean does the Treaty of Tordesillas line cross?

- Which territories of the American continent remained in the Portuguese zone?

- Why do you think Brazil today belongs to a Portuguese-speaking country?

- Why did Castile and Portugal need to sign an agreement before exploring new lands?

- Do you think it was fair that two European kingdoms divided territories where other peoples were already living? Explain your opinion.

- What consequences might this agreement have had for the rest of Europe?

Observe a current map of America. Identify which countries speak Spanish and which speak Portuguese. How is this related to the Treaty of Tordesillas?

Check

- 1492: first voyage of Christopher Columbus.

- Objective: reach Asia by a western route.

- Geographical error: ignorance of the existence of America.

- America: continent with advanced peoples and cultures.

- Treaty of Tordesillas: division of the Atlantic between Castile and Portugal.

- Consequence: beginning of European expansion.

7. Maya, Aztec and Inca: three great pre-Columbian civilizations

When Europeans arrived in America at the end of the 15th century, the continent was not empty. There were complex societies with cities, advanced agriculture, trade, systems of government and highly elaborate religions. Here you are going to learn about the Maya, the Aztecs (Mexica) and the Inca, and think like a historian: how do we know what we know?, what interests were there?, what changed with the arrival of the Castilians?

Clue: geography = history. Jungle, lakes and mountains influenced how each people lived.

Initial activity (5 min): “Source detectives”

- Write 3 things you think you know about Maya/Aztecs/Inca (even if you are not sure).

- Mark with ⭐ which one might be a stereotype or a myth.

- Say how you could check it: museum, remains, chronicles, drawings, maps…?

Objective: to learn that in History it always matters where the information comes from.

Check (introduction)

Which sentence is the most accurate?

The sages of the jungle

- Origin and duration: from c. 2000 BC; peak between 3rd–9th centuries.

- Politics: not a single empire; they were city-states (Tikal, Palenque, Copán…).

- Economy: agriculture (maize, beans, squash, cacao) and regional trade.

- Science: great observers of the sky; very accurate calendars.

- Culture: hieroglyphic writing and books called codices.

“Their flesh was made from yellow maize and white maize. Their arms and legs were formed from maize. Thus people were born, thus the strength of the human being was made.”

Clue: why is maize more than food? (identity, religion and economy).

Activity (critical thinking): why do great Maya cities “disappear”?

- Remains of cities covered by jungle.

- Inscriptions speaking of conflicts between cities.

- Climatic data indicating droughts in some periods.

- Which causes seem most likely to you: wars, droughts, exhaustion of resources…? Explain.

- Why is it difficult to have only one answer?

- What sources would you need to be more certain?

Write 5–6 lines with your hypothesis and one “piece of evidence” that supports it.

Check (Maya)

Mini-task (10 min): “A report from Tikal”

Write a short text (8–10 lines) as if you were a Maya messenger:

- Say what is happening in your city (festival, war, trade, construction).

- Mention 2 real elements: temples, observation of the sky, codices, maize.

- Finish with a sentence that shows their way of seeing the world (gods/nature/cycles).

The empire of the great city on the lake

- Legendary origin: migration from “Aztlán” and foundation of Tenochtitlán (c. 1325).

- Capital: great city with canals, causeways, markets and temples.

- Empire: based on war and on tributes from subjugated peoples.

- Society: emperor (Huey Tlatoani), nobles, priests, warriors, merchants, peasants.

- Agriculture: chinampas (cultivable islands) → high production.

“We were astonished to see so great a city in the middle of the water, with causeways and bridges, and markets full of people and merchandise. It seemed like something enchanted.”

Clue: this is a European testimony. What might it exaggerate? What might it describe accurately?

Activity (critical thinking): why did the Aztecs fall so quickly?

- Alliances: subjugated peoples who hated tribute.

- Diseases: epidemics that reduced population and defences.

- Politics: internal tensions and leaders’ decisions.

- Technology: military differences (but that does not explain everything).

- If you were a subjugated people, would you help Cortés? Justify with a “realistic” reason.

- Which factor seems most decisive to you: alliances, epidemics or weapons? Explain why.

- What part of this story may be told “in favour of” someone?

Write 6–8 lines: “The fall of the Aztecs is better understood if we think about…”

- Markets: massive exchange (food, textiles, tools).

- Cacao: it was used as a valuable product and also as a means of exchange.

- Tributes: the empire fed itself on what other peoples delivered.

- Religion: gods linked to nature; rituals to maintain the balance of the world.

Check (Aztecs)

Activity (10–15 min): “Simulate a market in Tenochtitlán”

- Choose 1 product: cacao / cotton / maize / salt / feathers / pottery.

- Write who produces it and who wants to buy it (peasant, merchant, noble…).

- Explain what problem appears if the empire demands very high tribute.

- Conclusion: how can a market “make a city strong”?

The engineers of the Andes

- Empire: the largest in America; called Tahuantinsuyo (“the four regions”).

- Capital: Cuzco, political and sacred centre.

- Organisation: provinces, officials and labour planning.

- Roads: huge network of routes; chasqui messengers.

- Agriculture: terraces and irrigation; potato, maize, quinoa.

“They had great roads across the mountains, with bridges and tambos (lodgings) to rest in. Thus they could carry messages and food throughout the whole kingdom quickly.”

Clue: what does an empire need in order to function? (transport, control, communication).

Activity (critical thinking): why was Pizarro able to capture Atahualpa?

- What is more dangerous for an empire: external enemies or a civil war? Explain.

- Why can capturing the leader disorganise a state?

- If you were an Inca official, what decision would you take to keep control?

Write 5–6 lines explaining how the internal context influenced the conquest.

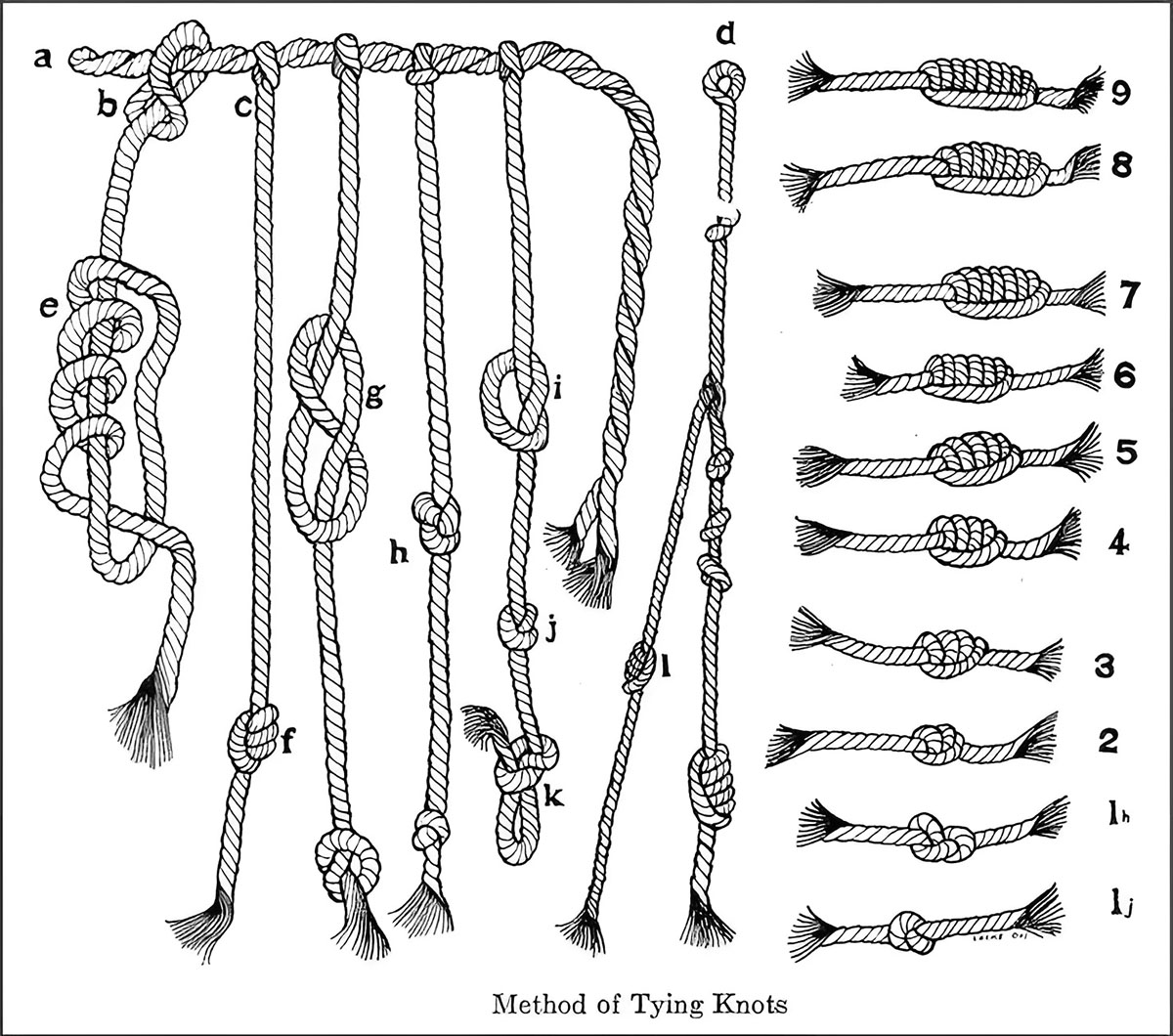

- Quipus: cords with knots to record data (population, tribute, storehouses).

- Terraces: mountain agriculture, preventing erosion and taking advantage of water.

- Communal labour: mita (for the State) and ayni (mutual help).

- Storehouses: reserves for difficult times or for the army.

Check (Inca)

Mini-challenge (10 min): “Design the empire”

On paper (or digitally), make a diagram with 4 arrows:

- Roads → for…

- Chasquis → for…

- Terraces → for…

- Quipus → for…

Conclusion: explain why a “well-organised” empire can expand further.

Final comparison: how are they similar and how are they different?

- Agriculture as a base (with techniques adapted to the environment).

- Important religion (rituals and calendars).

- Cities and elites (nobles/priests/leaders).

- Trade and exchange (local or imperial).

- Maya: many city-states; great writing and astronomy.

- Aztecs: tributary and military empire; huge lake capital.

- Inca: administration and road network; quipus and Andean terraces.

Critical thinking activity (15–20 min): “What would change if…?”

- Scenario A: If the Aztecs had not had enemy peoples, would the conquest have been more difficult? Why?

- Scenario B: If there had been no Inca civil war, would it have been just as easy to capture the leader? Explain.

- Scenario C: If the Maya had been a single united empire, would their resistance have changed?

“Because yes” is not valid: you must use one piece of evidence from the texts, images or lists in this section.

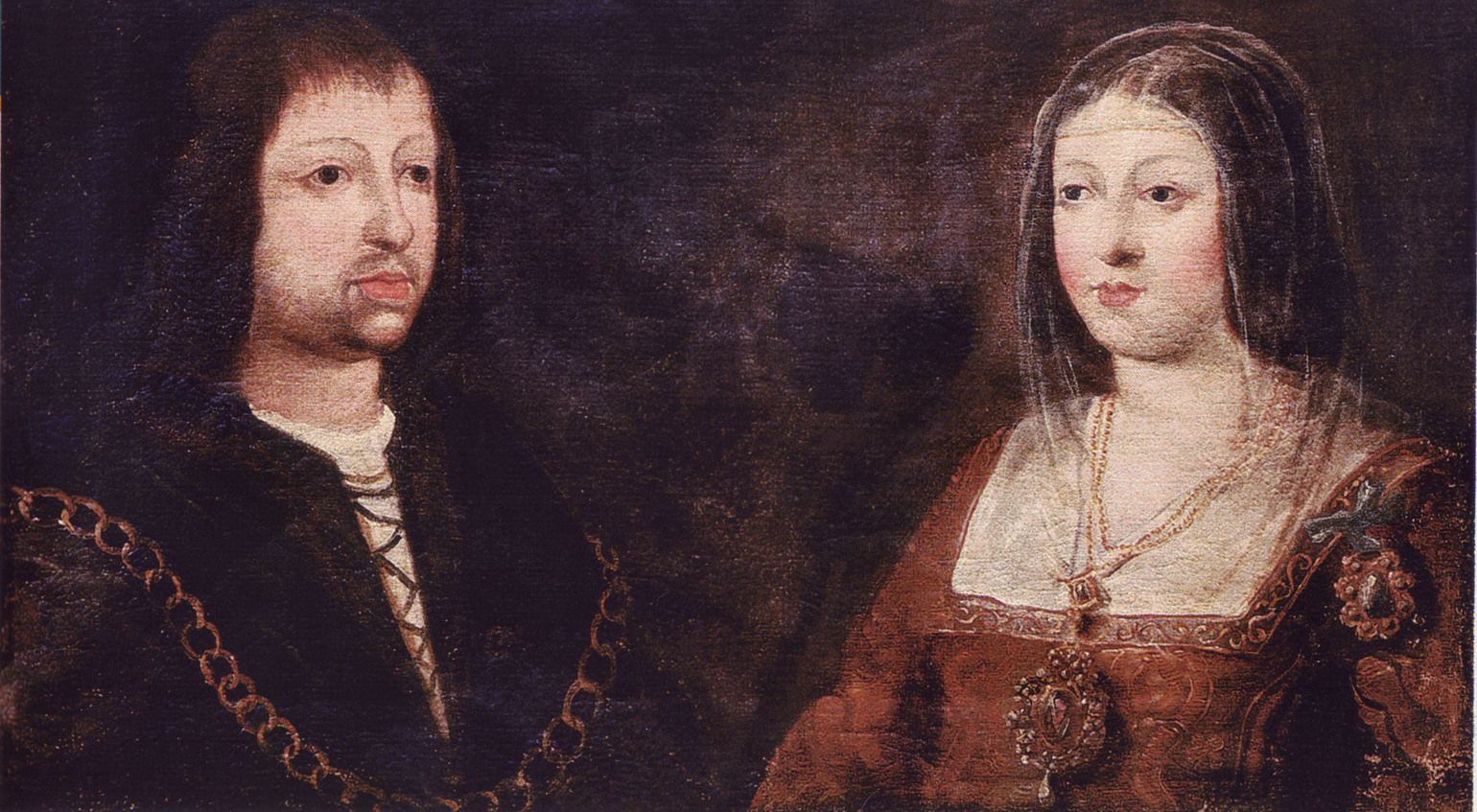

8. The birth of the modern state: the model of the Catholic Monarchs

At the end of the 15th century, some European monarchs consolidated their power against the nobility. They created permanent administrations, standing armies and more effective tax systems. Thus the authoritarian monarchy was born, the basis of the modern state.

Historical evidence 1: the strengthening of royal power

“We order that in all the cities, towns and places of our kingdoms the Holy Brotherhood be established to pursue thieves, robbers and other wrongdoers who disturb the public peace. We order that its officers may arrest and punish those who commit crimes on the roads and in uninhabited places, without any person, whether noble or powerful, being able to prevent their action. And we declare that said Brotherhood acts in the name of our royal authority, so that in our kingdoms there may be justice, security and obedience to the Crown.”

- What institution is mentioned?

- Who previously had control of justice in rural areas?

- What does it mean that even nobles cannot prevent its action?

- Why is it important that it acts “in the name of the king”?

- What relation does this have to the creation of a standing army? who has the final authority?

- What problem is it trying to solve?

- Whose power does this measure reduce?

- Is this only security or also political control?

Conclusion: Does this measure strengthen the king against the nobility? Explain how.

Historical evidence 2: administration and justice

“We order that in the principal cities and towns of our kingdoms there be a corregidor who represents our authority. Said corregidor shall administer justice in our name, enforce our laws and ensure that the councils and municipal officers act according to law. We order that no person, even if he is a knight or powerful lord, shall hinder his exercise or disobey his commands, for he answers directly to the Crown.”

- Who issues the rule?

- What function does the corregidor perform?

- On whom does he depend?

- Who loses power with this measure?

- Why is it important that the corregidor depends on the king?

- Why is this an example of centralization?

Activity: Map of power

Draw how power was organised in a city before the corregidor and after its implementation. Explain the change in 4 lines.

Political trial: Abuse of power or construction of the State?

Year 1480. A Castilian city is protesting. The king has sent a corregidor. Today a political trial is being held.

“We order that in the cities there be a corregidor who represents our authority and enforces our laws.”

It defends that the corregidor guarantees justice, order and unity of the kingdom.

It argues that the king invades traditional rights and concentrates too much power.

Must decide whether it is a necessary measure or political abuse.

Verdict

Does the corregidor strengthen the State or reduce local freedoms? Justify with historical evidence.

Diplomacy: the silent weapon

- Which kingdoms did they marry their children into?

- Which common enemy did they want to isolate?

- Why is marriage a political tool?

Check your understanding

Historical judgement

Did the Catholic Monarchs create a modern state or simply strengthen their personal power? Argue with at least 3 pieces of evidence taken from the previous texts.

- They created permanent institutions.

- They controlled justice and administration.

- They strengthened the army and diplomacy.

- They reduced the power of the nobility.

9. Social changes: the rise of the bourgeoisie

Society remains divided into estates, but the bourgeoisie gains power thanks to trade and banking.

- International trade.

- Banking (Medici, Fugger).

- Participation in urban governments.

They depended legally on their father or husband. Some stood out in art and religion.

Check

Competency-based activity

Draw a social pyramid of the 16th century and explain which group had the greatest real power.

10. A period of economic growth

During the 16th century, the population increases and the European economy grows. Agriculture improves, craftsmanship is transformed and Atlantic trade surpasses Mediterranean trade.

Agriculture

- Progressive end of fallow.

- Crop rotation.

- Greater production → larger population.

Domestic system

Merchants deliver raw materials to peasants. They produce at home. The entrepreneur sells the product.

- Less guild control.

- More production.

- Profit for merchants.

Historical thinking

Why did Atlantic trade end up becoming more important than Mediterranean trade? Relate it to America and precious metals.

11. Reformation and Counter-Reformation

In the 16th century Western Christendom broke apart. Criticism of the Catholic Church, driven by Martin Luther and other reformers, gave rise to new Christian denominations. In response, the Catholic Church promoted its own renewal: the Counter-Reformation.

“God’s forgiveness is not bought with money or papers; it is received by the one who turns to God from the heart. Whoever truly believes and repents already has the forgiveness he needs, without depending on preachers who promise quick salvation. Therefore, the Christian must place his trust in faith and in God’s grace, not in the business of indulgences.”

Check

Why did the Reformation arise?

- Sale of indulgences.

- Poor training of the clergy.

- Luxury of the higher hierarchies.

- Spread of the Bible thanks to the printing press.

12. Interactive activities

Review by playing.

13. EARLY MODERN AGE BREAKOUT

Put what you have learned to the test with an “escape room”-style challenge: clues, questions, and decisions to move forward. Ideal for reviewing contents on Humanism, the Renaissance, science, and explorations.

0 Comentarios